Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

South Asia and Afghanistan correspondent

Bbc

BbcGurprett Singh was handcuffed, his legs and a chain tied around his waist. It was led by the asphalt in Texas by the US Border Patrol to a C-17 waiting military transport aircraft.

It was February 3rd and after a monthly trip he realized that his dream of living in America was over. He was deported back to India. “I felt that the earth was slipping out of my feet,” he said.

The 39 -year -old Gurprett was one of the thousands of Indians in recent years, who spent their life savings and crossed continents to enter the United States illegally across their southern border as they sought to escape from the unemployment crisis at home.

In the United States, there are about 725,000 unodocucted Indian immigrants, the third largest group behind the Mexicans and El Salvadorets, according to the latest Pew Research data in 2022.

Now Gurpreet has become one of the first undocumented Indians to be sent home, as President Donald Trump has taken office, with a promise to make mass deportations priority.

Gurpreet intended to make a request for asylum based on threats he said he had received in India but – in accordance with Executive Order from Trump to divert people without “He said he had been removed without his work was never heard.

About 3,700 Indians were sent back to charter and commercial flights during the term of President Biden’s term, but the latest images of detainees in chains under the Trump administration have caused outrage in India.

The US border patrol has released images in an online video with a bombastic choir soundtrack and the warning: “If you go illegally, you will be removed.”

US borderline

US borderline“We sat with handcuffs and shackles for more than 40 hours. Even the women were tied in the same way. Only the children were free,” Gurpreet told the BBC back in India. “We were not allowed to stand up. If we wanted to use the toilet, we were accompanied by US forces and only one of our handcuffs was taken down.”

Opposition parties protested in parliament, saying that Indian deporteds were provided with “inhuman and humiliating treatment”. “There is a lot of talk about how Prime Minister Modi and G -n Trump are good friends. Then why do Modi allow this?” Priyanka Gandhi Vadra, a key leader of the opposition, said.

Gurparato said, “The Indian government had to say something on our behalf. They had to tell the US to deportation the way it was done before, without handcuffs and chains.”

A spokesman for the Indian Foreign Ministry said the government caused these concerns with the United States and as a result of subsequent flights, deported women were not handcuffed and chained.

But on Earth, the frightening images and the rhetoric of President Trump seem to have the desired effect.

“No one will try to go to the United States now along this illegal” donkey “route while Trump is in power,” Gurpette said.

In the longer term, this may depend on whether there is a continuation of deportations, but so far many Indian people who are referring locally called “agents” have been hiding, fearing attacks against them by Indian police.

Gurpette said the Indian authorities had asked for the number of the agent he used when he landed at home, but the smuggler could no longer be reached.

“However, I don’t blame them. We were thirsty and went to the well. They did not come to us,” Gurpreet said.

While the official title figure puts Unemployment rate of only 3.2%It conceals a more indelible picture for many Indians. Only 22% of workers have regular salaries, the majority are self-employed and almost fifth are “unpaid helpers”, including women working in the family business.

“We leave India only because we are forced. If I received a job that paid me even 30,000 rupees ($ 270/$ 340) a month, my family would have done.

“You can say what you want for the paper economy, but you need to see the reality on the spot. We have no opportunity to work or run a business here.”

Ghetto images

Ghetto imagesGupreet’s truck company was among the dependent on cash that was heavily affected when the Indian government withdrew 86% of the currency in circulation with four hours of notice. He said he didn’t pay him from his customers and had no money to keep the business in sailing. Another small business he created has managed logistics for other companies also failed because of Covid’s lock, he said.

He said he tried to make visas go to Canada and the United Kingdom, but his applications were rejected.

Then he took all his savings, sold a plot he owned, and borrowed money from relatives to raise 4 million rupees ($ 45,000/36,000 pounds) to pay the smuggling to organize his trip, Gurpett told us.

On August 28, 2024, he flew from India to Guyana in South America to begin a heavy trip to the United States.

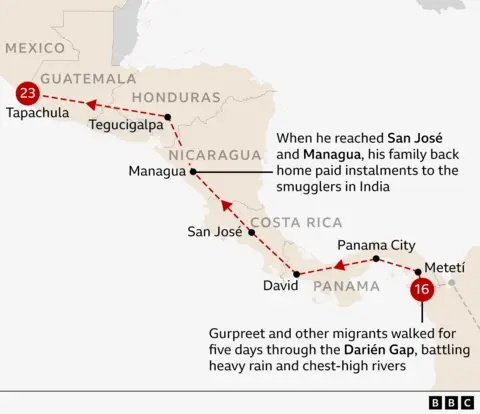

Gurpette pointed out all the stops he made on the map of his phone. From Guyana, he travels through Brazil, Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador and Colombia, most of all by buses and cars, partly by boat, and briefly on an airplane -handed over by one controller to another, detained and released by the authorities several times along the way.

From Colombia, smugglers tried to take his flight to Mexico, so he could avoid intersecting Darien’s fearsome gap. But Colombian immigration did not allow him to get on the flight, so he had to make a dangerous hike through the jungle.

The dense space of the tropical forests between Colombia and Panama, the Darin gap can only be crossed on foot, risking accidents, illnesses and attacks by criminal gangs. Last year, 50 people died, making the intersection.

“I wasn’t scared. I was an athlete, so I decided I was going to be fine. But it was the most difficult section,” Gurpette said. “We walked five days through the jungles and rivers. In many parts, as it walked through the river, the water approached my chest.”

Each group was accompanied by a smuggler – or Donker, as Gurpreet and other migrants refer to them, a word seemingly obtained from the term “donkey route” used for illegal migration trips.

At night, they would put tents in the jungle, eat some food they carried and try to rest.

“It was raining all the days we were there. We were watered to our bones,” he said. During the first two days, they were directed to three mountains. He then said that they should follow a route marked in blue plastic bags tied to smugglers.

“My legs started to feel like lead. The nails of the nails were cracked and my palms of my hands were peeled off and had thorns in them. We were still lucky that we did not meet any robbers.”

When they reached Panama, Gurpreet said that he and about 150 others were detained by border officers in a narrow center similar to the prison. After 20 days, they were released, he said, and from there it took him more than a month to reach Mexico, passing through Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Honduras and Guatemala.

Gurparato said they had been waiting for nearly a month in Mexico until they could cross the US border near San Diego.

“We did not scale a wall. There is a mountain near it that we climbed. And there is a razor wire through which Donner cut,” he said.

Gurpreet entered the United States on January 15, five days before President Trump took office – believing that he had done it just in time before the borders become impenetrable and the rules become more stringent.

Once in San Diego, he surrendered to the US border patrol and was then detained by immigration and customs law enforcement (ICE).

During the Biden administration, illegal or undocumented migrants will appear before an immigration employee who will interview a preliminary interview to determine whether each person has a refuge. While the greater part of the Indians have migrated from the economic need, some have also left Fear of persecution because of their religious or social origin or their sexual orientationS

If they cleared the interview, they were released, waiting for a refuge decision by an immigration judge. The process often takes years, but in the meantime they were allowed to stay in the United States.

This is what Gurprotte thought would happen to him. He had planned to find a job at a grocery store and then get into a transportation, a business he is familiar with.

Instead, less than three weeks after entering the United States, he turned out to be led to this C-17 aircraft and returned to where he started.

In his small house in Sultanpur Lodi, a city in the northern state of Pendjab, Gurpepet is now trying to find a job to pay the money he owes and takes care of his family.

Additional reporting from Aakriti Tapar